In this post, I want to explore how we might establish AI attribution frameworks and increase the transparency of provenance.

Tag: writing

Uplevel your prompt craft in ChatGPT with the CREATE framework

This post explores the various components of crafting high-quality prompts for different Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools like DALLE-2 and ChatGPT. I share the CREATE framework to communicate best practices and critical guidelines. The framework aims to help people write better prompts and improve their prompt craft skills.

5 Tips To Get Started with Reflective Journaling

Put Down Your Phone And Write

For the past few years, I’ve been documenting my reflections and experiences in a journal.

I use the Bullet Journal method, which is a simple notation system for the different entries. I like how it is forgiving and flexible, adapting to my various needs or lack of motivation.

Journals and notebooks have always been a part of my professional life, and I have plenty of volumes of scribbles, drawings and sketches.

Let’s have a look at the benefits of a habit of journaling regularly.

Benefits of reflective journaling

Journal writing is a way to get in touch with our thinking, feelings, memories and sense of self.

It can be introspective or analytical. It can also act as an aid for reflection on the past and thinking about the future. Journals provide a space to record thoughts, dreams and insights throughout different times in our lives.

Without the pressure of a more formal thinking style, I often find it easier to relate to different experiences and see the links between them.

The benefits of writing regularly about our thinking can bring about:

- An understanding of thinking patterns, both negative and positive, that we do every day.

- There is a greater sense of control because we get to choose the direction and topic/theme for each journaling session.

- Depth and flexibility of thinking.

- The act of writing itself can affect thinking patterns positively.

- There are clear links between regular journaling and increased self-awareness and understanding.

- Reflective journaling can lead to greater emotional intelligence because we become more aware of emotions, the triggers that cause them and how they affect thinking patterns.

- Journal writing enhances our introspection. It makes it easier for us to “know thyself”.

- Writing about past experiences can help us to understand how we have reacted and learnt from those situations.

- Journal writing can be a source of inspiration when future goals are being planned. It can also be a way to identify future opportunities that have been missed because we have not been attuned enough to our emotions, instincts or intuitions.

My Top 5 Journaling Tips for Getting Started

#1 — Splurge on Stationery

Educators have a secret love for new stationery. A school stationery cupboard is a special place. There is something wonderful about finding just the right pen or the quality of the heavy paper.

Use a notebook you like. It can be a simple colour, size or design that makes you feel good about writing in it every day.

My weapons of choice are a Micron 01 pen and a Leuchtterm Bullet Journal.

#2 — Keep your notebook nearby

You want to reduce the friction, so it is easy to build a habit. I keep my notebook open and with me all day, so it is easy to add and jot ideas down.

My notebook is on my bedside table too. This way, journaling can act as a “pre-sleep ritual” where you let thoughts flow freely and record them before the day is over. It is all about reflective habits and routines.

#3 — Write freely and worry less

Don’t worry about how you phrase things or what future actions you should take due to what you write. Write to express yourself first and foremost. If future opportunities or action items present themselves, that is a bonus.

Worry less about if you are doing journaling ‘right’. It is up to you.

#4 — Relax and have a biscuit

Make time for yourself every day to write in your journal. It can be at the beginning or end of each day or just as the day unfolds. Reflect on what has happened, dream about future possibilities and record insights as they appear.

Don’t worry too much about it if you find that writing is difficult after a busy day. Try again tomorrow or another time when you can relax and focus more quickly on your thoughts and feelings. I always find biscuits to help.

#5 — Don’t expect miracles

Journal writing is not a miracle cure. It has to become part of your life before you start to see the benefits. Like any ritual, it takes time to get in the habit and feel comfortable with it.

I have journals that span years because I didn’t write in them for months or think my practices were consistent. The future benefits are worth waiting for, even if you need to force yourself at the beginning!

“We must learn to ask questions, not of our future selves but of our present lives; we must ask what is the future that I am laying out for this one person called me.” ~ Annie Dillard

Your Talking Points

- What reflection framework suits your approach to journaling?

- Journaling does not need to be perfect; it only needs to happen.

- The benefits from journaling come from ongoing practice, so make it easy and flexible.

- How might your mindset or environment affect how quickly or easily you write in your journal?

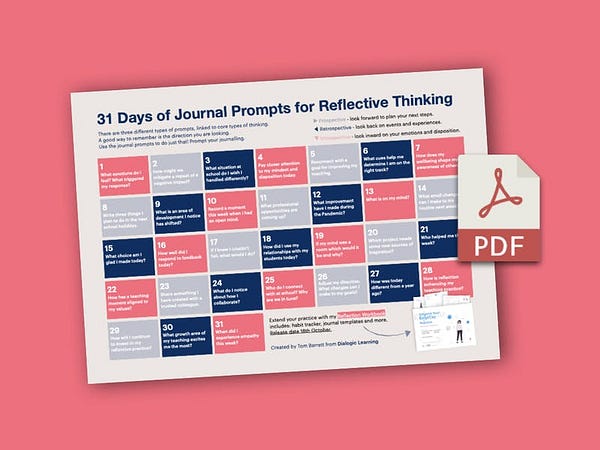

31 Days of Reflective Journal Prompts

My new Reflection Workbook is available now.

Download a free copy of my 31 Days of Reflective Journal Prompts to help you build a habit of healthy thinking and compound some gains about reflective practice.

Use the link below to visit the landing page and get your download.

Download A Month of Journal Prompts

My weekly email helps educators and innovation leaders enhance their practice by sharing provocations, ideas and mental models. Join today, and get your copy this week.

It does not matter how good the feedback is

When we are not ready to hear feedback, it does not matter how good the feedback is. This tension is a simple truth that often goes unnoticed during the process. That is why many of my tactics and strategies to improve feedback focus on how well we can receive it. It does not matter how good the feedback is.

During the process of creating something, we invest in different ways. Let’s say for this article; the creative process is a student working on writing a narrative piece that has a simple planning, drafting and editing process. But it could be anything: from a conference presentation you are making, a script you have been pitching, a product you are building or a jewellery piece you are designing.

Please extend these ideas into your context and consider how it is more important what you do with your feedback.

Once the task of crafting her story is shared, our student’s ideas will begin to bubble. For feedback to be useful, it should happen as early as possible. Depending on the learning design a student will invest in her writing in the following ways.

Factors Affecting the Response to Feedback

Cognitive effort

Is the work effortful? The challenge of planning and drafting a piece of narrative is quite broad. Our student invests cognitive energy in the problem. The levels of cognitive effort are likely to be very different for everyone. Some of us find it easy to develop slides for a presentation, whereas others have to invest more cognitive effort.

Perhaps what is more important here is the level of accumulated cognitive effort. In other words, how much thinking we have done. When feedback occurs at: “I have spent ages thinking about this.” it is received in a fundamentally different way to: “I have only just started thinking about this”.

Emotional Investment

When something is more meaningful to us, we want to commit. We cannot learn anything unless we care about it. Passionate commitment to a piece of writing is not always a part of the experience but given time; a writer will invest emotion into their work. When there is a high level of emotional investment, it is harder to hear critique.

Creativity

The ideas for the narrative piece need investment to get off the ground; creativity is the engine room. But over-investment in a poor plan is a harsh environment for feedback. There are lots of potential barriers to effectively hearing feedback here. For example, the first idea is considered the best approach or clutching too tightly to an idea even when it is a poor one.

Resources

Over time more and more resourcing is brought to a project. Tasks that have unlimited resources from the very beginning often lead to overcommitment. Should we be using every pencil in the set?

Accumulated Time

My reference here is the quantity of time that our student spends on her work. This amount accumulates as the work progresses and as the project continues. We are often far less inclined to action feedback when we have committed hours and hours to a version.

Here is another set of ideas that change throughout a creative task such as writing.

Fidelity

Although messy in reality, the path of a creative task is towards higher and higher fidelity. Let’s define fidelity as to how close the outcome is to the original concept. As time and effort accumulate, we would like to think that we are approaching a higher fidelity. At which point do we stop hearing feedback?

Opportunities to fail

Stakes get higher as opportunities to fail reduce. This is closely related to the amount of time that has passed and how long a student has been working on a piece of writing. Commitment to a “final” product or draft is crossed, and any significant changes or large scale feedback is difficult to action.

It is worth noting here that this could be a perception and have no grounding in reality. A student may incorrectly perceive they cannot start again or change their work at a late stage. It might not be ideal, but it may only be a perceived constraint. The second order effect is the stakes get higher.

Opportunities for formative evaluation

As stakes get higher, opportunities to fail reduce (perceived at least) and opportunities of formative assessment reduce. The word “formative” has a time stamp on it. Developmental evaluation should be happening as the writing begins to grow. Think of a more frequent reference to our “formative years’: that time in our life when we were learning life lessons.

Convergent and Divergent Mindsets

At the very centre of this is the disposition of the feedback receiver. Typically the mindset is somewhere on the Convergent – Divergent scale. As we decide on ideas and as our commitment or effort increase so our disposition shifts to Convergence. We rally around a core idea and push on. Our thinking becomes narrow as opposed to the expansive open thinking we should have done to get started.

Remember, this is a critical shift and one that allows us to execute creative work and not just deliver a hot mess of ideas. When it comes to the conditions for effectively receiving feedback, we might assume we need to be in a divergent state. But that is not always the case – the feedback needs to match the disposition state.

If I am refining a single idea and the intricate detail within it, I do not need other more significant ideas that might replace it. We have to be aware of the mindset of the receiver of feedback and carefully adapt what is shared.

The exception to this is always having an open disposition to feedback regardless of when it occurs. In my experience, what is coupled with this is a well-established feedback filter. After all, just because it is shared and we have received it, does not mean we need to do anything with it. We can still be open to late feedback when we are narrowly executing an idea.

Late and Early stage feedback

Let’s map these variables and how their levels of investment increase or reduce over the course of a project.

Formative evaluation needs to happen early on in a project arc. This allows the receiver of feedback to be most ready to hear it. Our student’s mindset is more open or divergent, and they are more likely to action new ideas.

Late stage feedback can still be invaluable, but we have to raise a red flag and be aware that receiving the feedback may be more challenging, requiring a much higher level of skill.

Practical Strategies

Here are five strategies that emphasise early feedback and ways to mitigate some of the challenges we have explored in this article.

- Design the feedback process – take your time to consider the frequency and type of feedback that is going to be shared. Intentionally design feedback opportunities.

- Design “low investment” creative tasks – increase the constraint on creative tasks at the beginning. Work on whiteboards or post-it notes rather than impressive graphic organiser, work with thick marker pens rather than every pencil in the set. Develop ideas on the back of a napkin, literally and metaphorically.

- Create opportunities for early feedback – a tonic to many of these challenges is to design as many options for initial input as possible. Early in the process, we are more likely to have an open mind to critique.

- Explore a range of ideas – work to develop a wide range of designs. We tend to have a bias towards our first idea. With little constraint, we might overcommit. Practice the thoughtful exploration of various concepts. Crazy 8s is always a good starting point.

- Match the feedback type to the point in the process – a critical insight I want you to take away is that feedback is received in very different ways. Attempt to match the feedback to the person receiving it and their journey. (Learn more about this in my article about 30% and 90% feedback.)

Despite the best intentions of the feedback provider, their high skill levels and even high quality – unless the receiver is ready to receive, it does not matter. Mitigate this by using some of these practical strategies and considering how we might increase the capacity, readiness and disposition of receiving feedback.

Photo by Efren Barahona

Find a Doorway That Fits Us Both

I grew up reading Stephen King and I recently stumbled on some of his advice and tips for writing.

He has authored over 100 books and one piece of wisdom that resonated strongly with me was to write a compelling first line, but not just as advice for writing.

“There are all sorts of theories,” he says, “it’s a tricky thing.” “But there’s one thing” he’s sure about: “An opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know about this.”

Stories are like worlds that we are invited into – they possess their own rules and laws, in the same way games draw you in. Stories are part of play and maybe an instigator of it or an extension.

[Children] negotiate and choose and build together under what seem to be a silent set of rules encoded deep inside them. The social aspect of immersive physical play just feeds the imaginations at work and you see worlds evolve and collapse, characters develop and disappear in quick succession.

[From In A World of Their Own – the features of immersive play]

As King suggests the first line is an invitation. As a teacher this might be the first interaction in a school day, or the opening activity of a period of learning. Crucial moments to draw learners in and engage their curiosity.

But Stephen King also states how important it is for the writer to orientate themselves, as it would be for the teacher – finding places where we can start learning together.

We’ve talked so much about the reader, but you can’t forget that the opening line is important to the writer, too. To the person who’s actually boots-on-the-ground. Because it’s not just the reader’s way in, it’s the writer’s way in also, and you’ve got to find a doorway that fits us both.

#28daysofwriting